Defining Child Stunting

Child stunting is the failure of children to reach their full growth potential as a result of long-term poor diet, health, and/or care, including emotional support. Stunting is identified and measured based on children’s height in relation to their age. It is a marker of a child’s overall lack of health and well-being, and is associated with limits to a child’s physical and cognitive potential.

Stunting is caused by factors throughout childhood, but primarily during the “first 1,000 days”—the period just before conception (when the mother’s nutritional status is of paramount importance) to a child’s second birthday. The impact of the poor diet, health, and care that lead to stunting, however, lasts far beyond childhood. The physical and cognitive consequences are largely irreversible, despite parents’ best efforts later in the child’s life. For the most part, stunting itself cannot be treated, only prevented. While there is ongoing debate about the importance of stunting as an outcome in itself versus a marker of other challenges, the importance of addressing the drivers of stunting is indisputable.

A child is considered stunted if their height-for-age z-score is more than two standard deviations below the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards median. This cutoff is a statistical metric rather than a biological condition; children just above and below the cutoff face similar risks. As such, these growth standards are more useful as a measure of a population’s health and nutritional status than for an individual child.

HAZ scores: normal distribution

The scale of the challenge

Percentage of children under the age of 5 who are stunted

An estimated 22 percent of children under five (144 million children) were classified as stunted in 2020. About 87 percent of these stunted children are clustered in low- and lower-middle-income countries. South Asia has the highest number of stunted children in the world, with nearly two out of five of all stunted children living in the region. While stunting prevalence has declined globally from 33 percent in 2000 to 22 percent in 2020, progress has been uneven, and the absolute burden has remained high (it has even increased in Africa as a result of population growth).

Implications for Individuals and Societies

Stunted growth casts a shadow over a child’s future. Child stunting is strongly associated with lifelong reduced cognitive abilities and poor health. Compared with a healthy child, a stunted child is more likely to have poorer educational outcomes, earn lower wages, and eventually have children who are themselves poorly nourished.

Multiplied by thousands or millions of children in a country, stunting is associated with increased health costs and reduced economic growth. Studies have estimated that the child health and development challenges associated with stunting can cost countries between 2 and 10 percent of their gross domestic product (GDP) annually. Countries with high stunting prevalence, also burdened by less educated and healthy workforces, are inadequately equipped to compete in the knowledge economy.

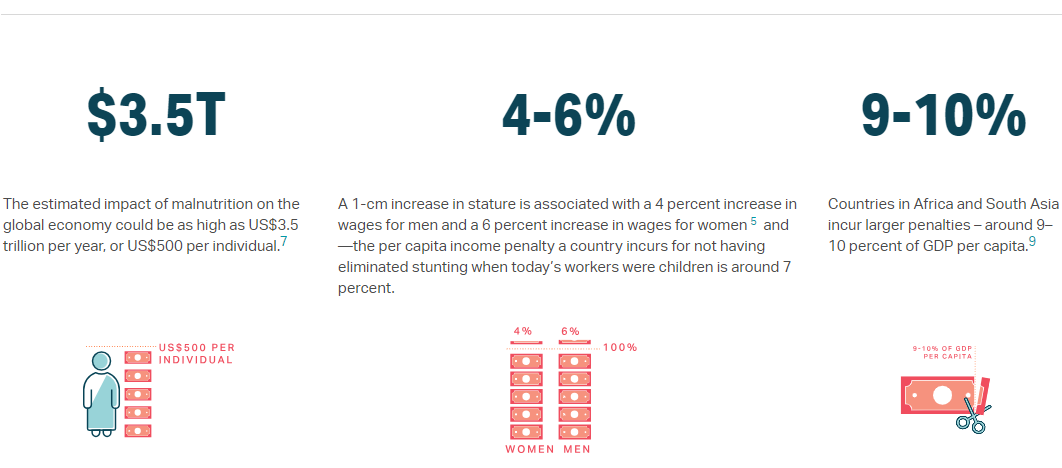

- The estimated impact of malnutrition on the global economy could be as high as US$3.5 trillion per year, or US$500 per individual.

- A 1 -cm increase in stature is associated with a 4 percent increase in wages for men and a 6 percent increase in wages for women6 and –— the per capita income penalty a country incurs for not having eliminated stunting when today’s workers were children is around 7 percent.

- Countries in Africa and South Asia incur larger penalties –— around 9 to -10 percent of GDP per capita.